Bart van der Leck (1876-1958)

Bart van der Leck remains the least known artist of the De Stijl. Like Mondrian, he was over forty when he finally developed the characteristic abstract style for which he is celebrated today. Aloof and opiniated, Van der Leck kept the artworld at arm’s length, forming few close friendships. Aside from his student years in Amsterdam, he lived outside cultural centers, rarely participating in exhibitions. His work was scarcely seen abroad as travel did not appeal to Van der Leck, who seldom left his home and studio. Supported by Helene Kröller-Müller and her advisor H.P. Bremmer, Van der Leck’s work found a home in the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo.

The son of an often-unemployed house painter, Van der Leck grew up in the slums of Utrecht as the fourth of eight children, only half of whom survived to adulthood. Schooled only until the age of fourteen, he apprenticed in a stained-glass workshop during Utrecht’s neo-Gothic building boom at the end of the nineteenth century. This experience proved pivotal to Van der Leck’s artistic development: perceiving color as light, defined by stark contrasts and bold simplicity. After eight years, Van der Leck earned a scholarship to Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, where his talent was recognized by August Allebé.

Architect and furniture maker Piet Klaarhamer (1874-1954), known as Gerrit Rietveld’s innovative instructor, was instrumental in Bart van der Leck’s early career in Utrecht. Despite their differing social standings, Klaarhamer introduced Van der Leck to a world of theology, philosophy, and poetry, expanding his intellectual horizons. These new ideas distanced Van der Leck from the Christian doctrine of his youth, replacing them with progressive political and mystical ideologies typical of the turn of the century. From 1904 to mid-1906, Van der Leck and Klaarhamer shared a studio in Utrecht, benefiting the synergy of their collaboration. Klaarhamer, an early and avid supporter of Van der Leck, owned The Adoration of the Christ Child, now in the Harvard Art Museum.

In 1908, Klaarhamer married Titia (Tjitske) Klein and they lived above her brother’s shop in Utrecht. Fokke Klein, a tea and coffee merchant from Harlingen, Friesland, commissioned Van der Leck to design logos for his roasteries across the Netherlands, a sort of Starbucks avant la lettre. The Utrecht shop was managed by Titia and her older sister, Baukje Klein, the first owner of Wise Virgins.

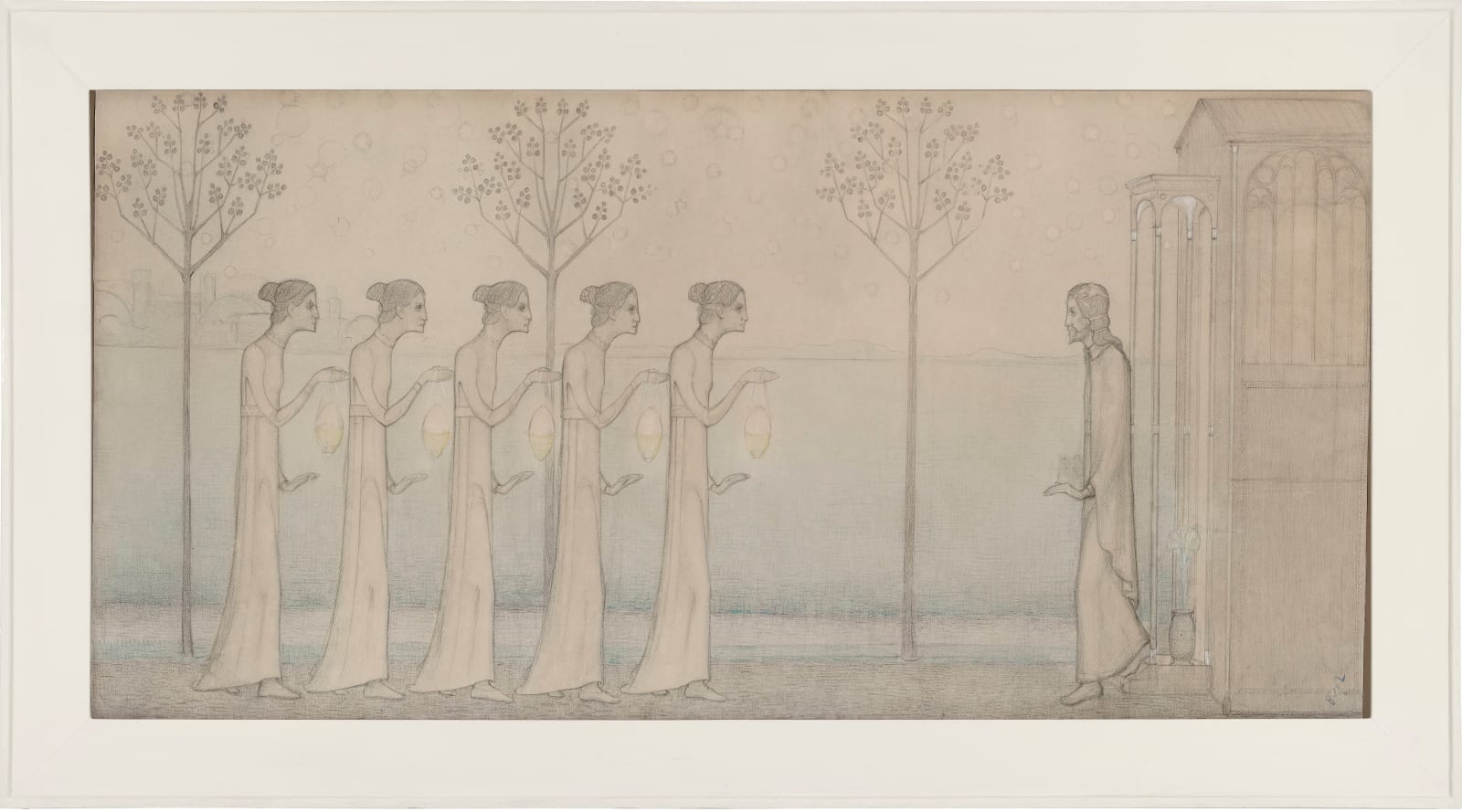

Whether Baukje commissioned this monumental drawing based on the Parable of the Ten Virgins from Matthew 25:1–4 remains uncertain. Van der Leck’s fascination with the theme is apparent from two preliminary sketches in the Kröller Müller Museum. A procession of five girls, dressed in a blend of medieval and Egyptian attire with glowing oil lamps in tow, journey to meet their Prince of Peace under a shimmering starry sky. The image exudes spiritual readiness, with the foolish virgins symbolically erased, the Wise Virgins emphasize the moral power of vigilance. The absence of the foolish virgins may commend Baukje, an unmarried independent woman who may have felt connected with the determined bridesmaids.

Provenance

Baukje Klein (1866-1939), Utrecht, by descent

Private collection, Utrecht

Their sale, Onder de Boompjes, Leiden, 19 June 2023, lot 16