Willem van Konijnenburg (1868-1943)

Further images

Together with Jan Toorop, Leo Gestel and Jan Sluijters, the Hague artist Willem van Konijnenburg represented the face of Dutch modern art abroad during the Interbellum. In his youth, Van Konijnenburg was famous not so much for his artistic skills as for his dandy-like appearance and his active involvement in The Hague art circles. From 1900 on, he abandoned The Hague School Impressionism and started to develop his own classical idiom. Using an invented system of rules in which symmetry and mathematical patterns played an important role, Van Konijnenburg created harmonious compositions, which won him considerable fame. His theme was no longer landscape, but the idealized individual. Van Konijnenburg’s unique interpretation of modern art was considered highly innovative at the time. He received important commissions, among them the relief in Berlage’s Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and participated in numerous exhibitions.

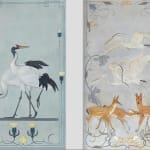

The present painting was only known from a list Konijnenburg assembled of the best works he produced between 1882 and 1908. One of the two paintings reminds us of the painting with three deer in Mrs. Kröller-Müller’s private residence, Jachtslot Sint Hubertus, one of the most iconic buildings in the Netherlands by renowned architect H.P. Berlage (1856-1934). Although stipulated by Berlage that this country house, for which he designed the interiors and furniture, was a Gesamtkunstwerk void of any other artwork, Konijnenburg’s painting must have been the exception since it prominently adorns the majestic dining room.

However, when Konijneburg painted the present two paintings the following year, the animal’s natural habitat was replaced by a decorative scheme of art nouveau ornamentation against a monochrome background. Inspired by eighteenth century Japanese woodblock prints or screens, Konijnenburg leaves traditional representation behind for Japonism, fashionable at the time. Like Vincent van Gogh, Konijnenburg’s sensibility drastically changed once he encountered these exotic and colorful artworks from the east, inspiring to make a contribution to modern art. The Japanese cranes inhabiting both paintings also further emphasize the connection to the East. The silver paint used for the ledge on which the cranes balance is also referencing Japanese screens.